Diagnosis

Presentation of cSCC

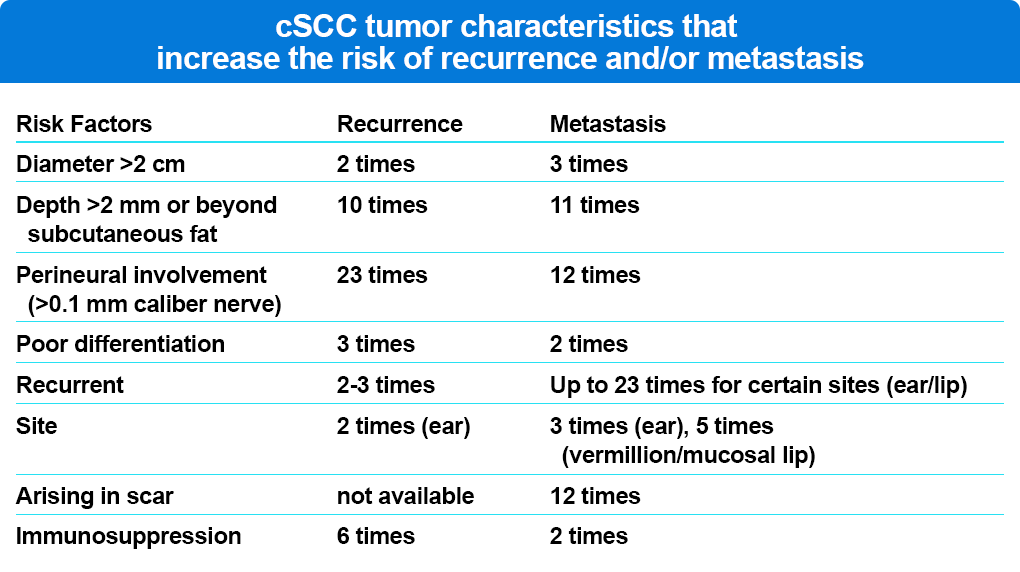

cSCC presents as a red, scaly plaque, typically in sun-exposed areas. Lesions are usually solitary; however, they can occasionally present as multiple “in transit” metastases. A tumor diameter greater than 2.0 cm doubles the risk of cSCC recurrence and triples the rate of metastasis compared with lesions less than 2 cm in diameter (Table 1). Tumor diameter greater than 2 cm is the risk factor most highly associated with disease-specific death, conferring a 19-fold higher risk compared with tumors less than 2 cm.

A patient with at least one cSCC is at risk for additional cSCC and other for skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma and melanoma. The 5-year probability of another non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) after diagnosis of a first is 40.7%; the 10-year probability is 59.6%; and after 2 or more occurrences the 5- and 10-year probabilities rise to 82% and 91%, respectively. After a diagnosis of local SCC, the NCCN guidelines suggest follow-up and screening every 3 to 12 months for 2 years after initial diagnosis, every 6 to 12 months for 3 years, then annually for life. For regional disease, suggested follow-up is every 2 to 3 months for 1 year, every 2 to 4 months for the second year, every 4 to 6 months for the third year, and then every 6 to 12 months for life. Concurrent patient and family member self-surveillance for cSCC and other skin cancers may be of additional utility in detecting new primary tumors.

cSCC Risk Factors

The presence of actinic keratoses (AKs) on sun-damaged skin is one of the strongest predictors of cSCC in unaffected people, and although a very small proportion of AKs are cSCC precursors, the true rate of malignant transformation of AKs is unknown. Although benign, numerous AKs increase an individual’s risk of cSCC, BCC and melanoma. Rates of progression from AK to cSCC have been widely reported from 0.025% to 10% per AK lesion per year to 0% to 0.075% per lesion per year. Two recent studies have documented the increased risk of cSCC in renal transplant patients, with one reporting cSCC to be four times more likely to develop in recipients who had confluent areas of actinic damage and the other noting that the presence of AK patches increased the risk of cSCC by 18-fold in the ensuing 18 months. Other risk factors for cSCC include glucocorticoid use, chemical exposures, and cigarette smoking, with weak relationships for human papilloma virus and high body mass index. Other well established cSCC risk factors are indoor tanning and immunosuppression as demonstrated by the high cSCC rates in both individuals with any exposure to indoor tanning (increases risk by 67%) and organ transplantation. With knowledge of these risk factors, it is important to identify and diagnose cSCC early in the disease course for the most favorable outcomes.

References

Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, Leigh I. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019,20,2009.

Dodds A, Chia A, Shumack S. Actinic keratosis: rationale and management. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2014; 4: 11-31.

Ducroux E, Boillot O, Ocampo MA, et al. Skin cancers after liver transplantation: Retrospective single-center study on 371 recipients. Transplantation. 2014;98: 335-340.

Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348: 1681-1691.

Geidel G, Heidrich I, Kott J, et al. Emerging precision diagnostics in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022;6(1):17.

Green AC. Epidemiology of actinic keratosis. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2015;46: 1-7.

Green AC, Olsen CM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: An epidemiological review. Brit J Dermatol. 2017;177: 373-381. doi:10.1111/bjd.15324

Jiyad Z, O’Rourke P, Soyer HP, Green AC. Actinic keratosis-related signs predictive of squamous cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients: A nested case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4): 965-970.

Johnson MM, Leachman AS, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: Recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4: 13-37.

Quaedvlieg PJ, Tirsi E, Thissen MR, Krekels GA. Actinic keratosis: How to differentiate the good from the bad ones? Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16: 335-339.

Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152: 419-428.

Ulrich C, Kanitakis J, Stockfleth E, Euvard S. Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients–where do we stand today? Am J Transplant. 2008;8: 2192-2198.

Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clinic North Am. 2019;33: 1-12.

Wallingford SC, Russell SA, Vail A, et al. Actinic keratosis, actinic field change and associations with squamous cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients in Manchester, UK. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95: 830-834.

Wehner MR, Linos E, Parvataneni R, Stuart SE, Boscardin WJ, Chren MM. Timing of subsequent new tumors in patients who present with basal cell carcinoma or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatology, 2015;151; 382-388.

Wehner MR, Cidre Serrano W, Nosrati A, et al. All-cause mortality in patients with basal and squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78: 663-672.

Whelass L, Black J, Alberg AJ. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and the risk of second primary cancers: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19: 1686-1695.