What is cSCC?

Non-melanoma skin cancers are the most common form of skin cancer worldwide, with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) being the second most common type.1,2 Affecting over 2 million people globally, the incidence of cSCC has seen a dramatic increase of 310% between 1990 and 2017.1,3

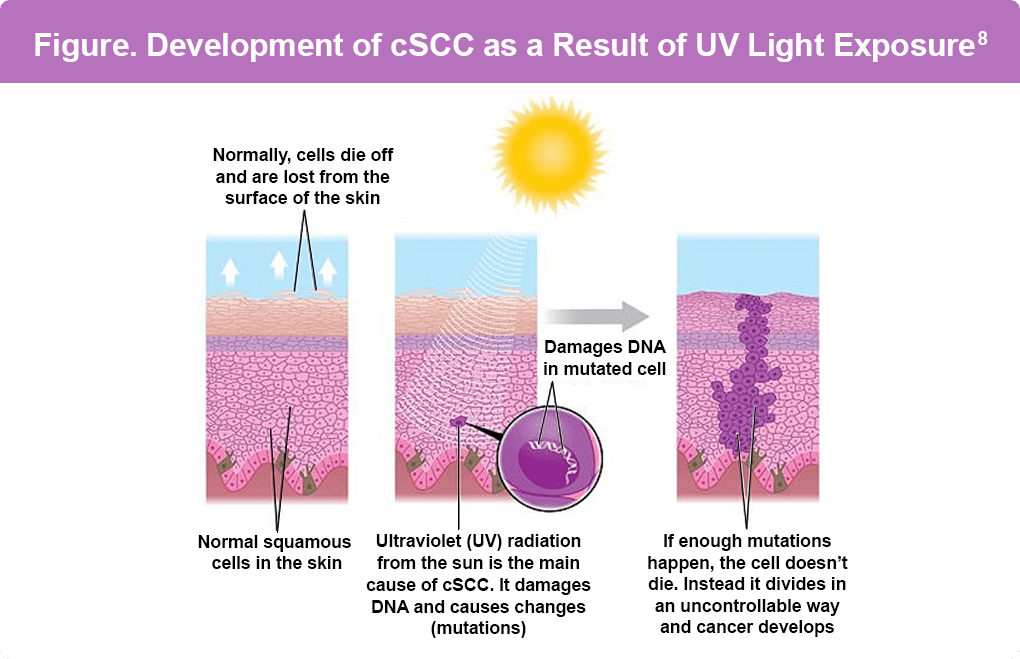

cSCC is a type of cancer that starts in the cells of the outer layer of the skin, known as the epidermis (Figure). It typically develops on skin areas that have been exposed to natural or artificial sunlight over long periods of time, including the face, ears, lower lip, neck, arms, and back of the hands. Additionally, it may occur on skin that has been burned or exposed to chemicals or radiation.4

These cancers can appear as5:

- Rough or scaly red (or darker) patches, which might crust or bleed

- Raised growths or lumps, sometimes with a lower area in the center

- Open sores (which may have oozing or crusted areas) that don’t heal, or that heal and then come back

- Wart-like growths

- A flat area showing only slight changes from normal skin

Risk Factors

Research has established that exposure to sunlight significantly increases the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC).6 cSCC typically appears on sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the face, ears, neck, lips, and backs of the hands, but can also develop in scars or chronic skin sores. Individuals with fair hair, skin, and eye color who have experienced excessive sun exposure are at the highest risk of developing cSCC.7 A strong correlation exists between chronic sun exposure, the number of site-specific sunburns, total site-specific exposure, and the development of cSCC. Consequently, cSCC rates are higher among individuals with outdoor occupations, with the risk increasing with age.

Certain medications can increase the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). These include9:

- Immunosuppressive Agents and Antimetabolites: Mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine A, and cyclophosphamide

- Diuretics: Hydrochlorothiazide

- Antifungal Medication: Voriconazole, especially among lung or hematopoietic transplant patients

- JAK Inhibitors: Ruxolitinib, used for myelofibrosis or polycythemia, with cases appearing as early as 11 months after starting therapy

- Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors: Vismodegib, previously shown to increase cSCC risk but recent studies are inconclusive

- BRAF Inhibitors: Used in metastatic melanoma treatment, with 19%–26% of patients developing cSCC. Combining these with MAPK kinase inhibitors (MEKi) has shown potential in reducing this risk

Additional risk factors include being male, exposure to certain chemicals (arsenic, coal tar, paraffin, certain types of petroleum products), exposure to radiation, previous skin cancer, long-term or severe skin inflammation or injury, and certain genetic syndromes (Epidermolysis bullosa, Fanconi anemia, Muir-Torre syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, Bloom syndrome, and Werner syndrome).10

References

- Chong CY, Goh MS, Porceddu SV, Rischin D, Lim AM. The current treatment landscape of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:25-40. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00742-8

- Rentroia-Pacheco B, Tokez S, Bramer EM, et al. Personalised decision making to predict absolute metastatic risk in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: development and validation of a clinico-pathological model. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;63:102150. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102150

- Urban K, Mehrmal S, Uppal P, Giesey RL, Delost GR. The global burden of skin cancer: A longitudinal analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990-2017. JAAD Int. 2021;2:98-108. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.10.013

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. (https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma).

- American Cancer Society. Signs and Symptoms of Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers. Last revised October 31, 2023. (https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-and-symptoms.html).

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Solar and Ultraviolet Radiation. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1992. Iarc Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 55. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK401588/).

- Sitek A, Rosset I, Żądzińska E, Kasielska-Trojan A, Neskoromna-Jędrzejczak A, Antoszewski B. Skin color parameters and Fitzpatrick phototypes in estimating the risk of skin cancer: A case-control study in the Polish population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:716-723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.022

- Karger. The Waiting Room. What Is (Advanced) Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma? April 13, 2022 (https://thewaitingroom.karger.com/tell-me-about/what-is-advanced-cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma/).

- Jiang R, Fritz M, Que SKT. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: An Updated Review. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:1800. doi:10.3390/cancers16101800

- American Cancer Society. Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancer Risk Factors. Last revised October 31, 2023. (https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html).

All URLs accessed September 16, 2025